TABLE Magazine continues its art of the staycation series with a visit to the historic inn, spa and organic farm at los poblanos.

The last few years have been stressful as we struggled to maintain our health, jobs, families, and sanity. Besides hearing “you’re on mute” in countless Zoom meetings, another phrase echoed frequently: self-care. Self-care looks different for everyone—reading quietly, sipping wine in the bathtub, or binging a favorite TV show. For me, it also means a staycation with my best friend to a beautiful hotel featuring a spa, pool, restaurant, bar, and expansive grounds. However, most importantly, a wellness yurt for morning yoga. Los Poblanos Historic Inn & Organic Farm, located in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque on 25 acres of lavender fields and gardens, fulfills all of these desires.

Staying at Los Poblanos Historic Inn

Upon checking in on a recent Friday afternoon, the scent of lavender immediately welcomed us. We admired the talents of the Inn’s 1930s architect, John Gaw Meem, as we dropped our bags in the North Field room. Located north of the lavender fields, the room was large and charming, with crisp white bedding, Spanish colonial-style décor, a wooden wet bar, and a comfortable patio overlooking artichokes and sunflowers.

The sun was hot. Very hot. We quickly changed into our bathing suits and headed to the outdoor saltwater pool at the center of the guest facilities. The pool attendant offered striped beach towels and a cocktail list. We ordered lavender margaritas, tequila cocktails with a lavender-sugar rim, perfect under the relentless afternoon sun. As dark thunderclouds gathered, we carried our drinks back to the patio and sipped silently, appreciating the Southwest rain.

Dining at Campo

We changed into summer linen and made a short, rainy sprint to Campo bar and restaurant. While waiting for our dinner reservation, we enjoyed the Nosh Board, a charcuterie platter of meats and cheeses drizzled with 22-year-old Monticello Balsamico, which balanced the fruitiness of the cheese and elevated the cured meats. Paired with sparkling Blanc de Noir from Gruet, it was a perfect start.

Seated on the Campo patio, we ordered a bottle of 2018 Atamisque Malbec from Valle de Uco, Argentina, alongside Braised Lamb Birria and native beef strip loin. The lamb birria, stewed in chili and spices, arrived with vegetables, blue corn hominy, and a warm wheat tortilla to soak up the broth. The beef was coated in salsa macha made from toasted chili, garlic, oil, and sesame seeds, served with roasted potatoes and vegetables. Both dishes were spicy and warming on a cool, damp evening. Dessert included an exceptional crème brûlée paired with Fonseca 20-year Tawny Port from Portugal. Campo shares recipes for its Lavender Margarita and Lamb Birria as well.

Morning Yoga and Farmers’ Market

By morning, the rain had stopped, leaving drops glistening on the hollyhocks. We headed to a gentle yoga class in the Wellness Yurt, nestled among tall trees on the south side of the property. The tent’s skylight and bay windows brought nature into our practice. Los Poblanos provided mats, blankets, and blocks arranged in a circle. The hour-long session emphasized breathing, moderate stretching, and fundamental techniques, helping us relax and unplug.

Later, we borrowed cruiser bicycles and rode to the Los Ranchos Farmers’ Market. This small market offered produce, foods, and crafts—from Mexican spring onions and tomato plants to local honey and glass hummingbird feeders. We sipped cucumber-mint lemonade, nibbled homemade cheese pastries, and listened to classical guitar music. The scene felt idyllic and small-town perfect.

Spa Bliss at Hacienda Spa

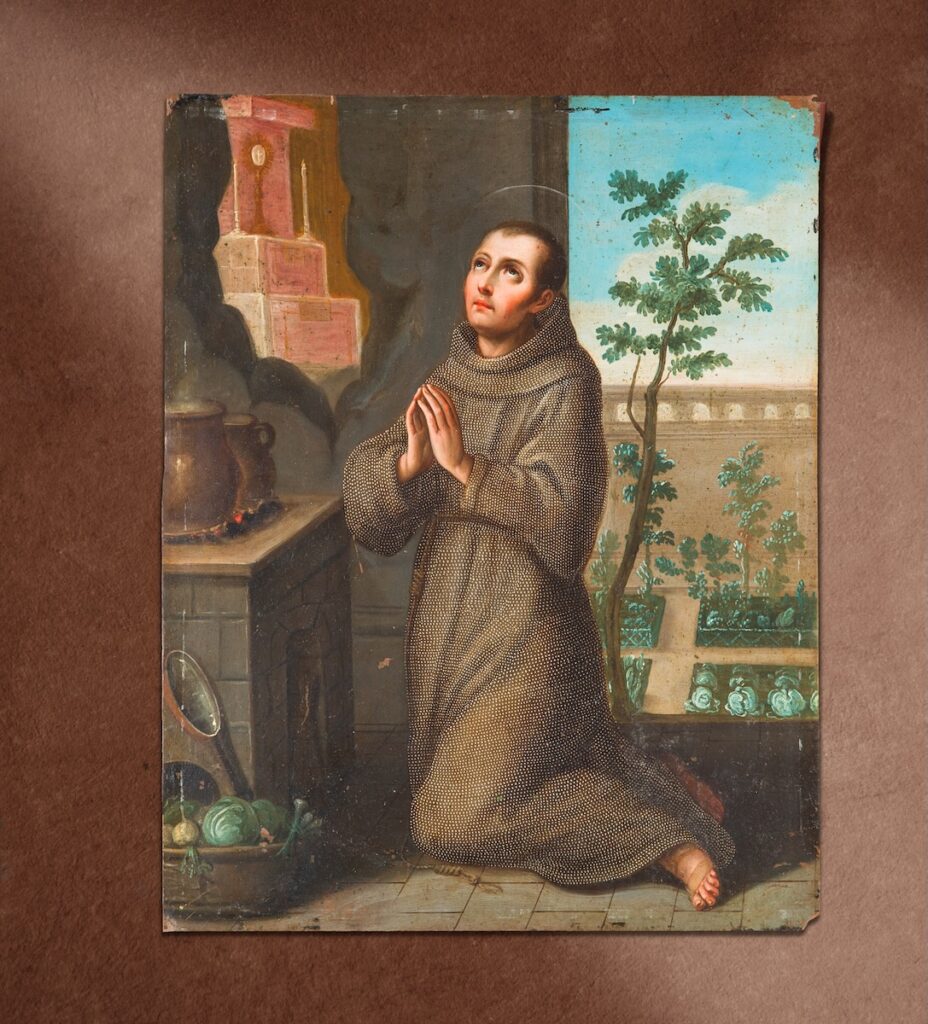

Back at Los Poblanos, we indulged in a therapeutic massage and dry body scrub at the Hacienda Spa, housed in the original family home designed by Meem. The changing room featured dove-gray robes, slippers, and painted panels by Paul Lantz, transporting us to a glamorous, F. Scott Fitzgerald-inspired world.

In the waiting lounge, we relaxed near the fireplace, whose mantel reads, “and that upon honesty of work depends.” Lavender essential oils scented the massage room. The exfoliation began with circular motions to slough off dead skin, followed by a Swedish-style therapeutic massage. After 50 minutes, we were led to the interior courtyard. This is where we were sipping cherry-infused water while lounging under umbrellas and enjoying the star-shaped fountain.

Exploring the Grounds

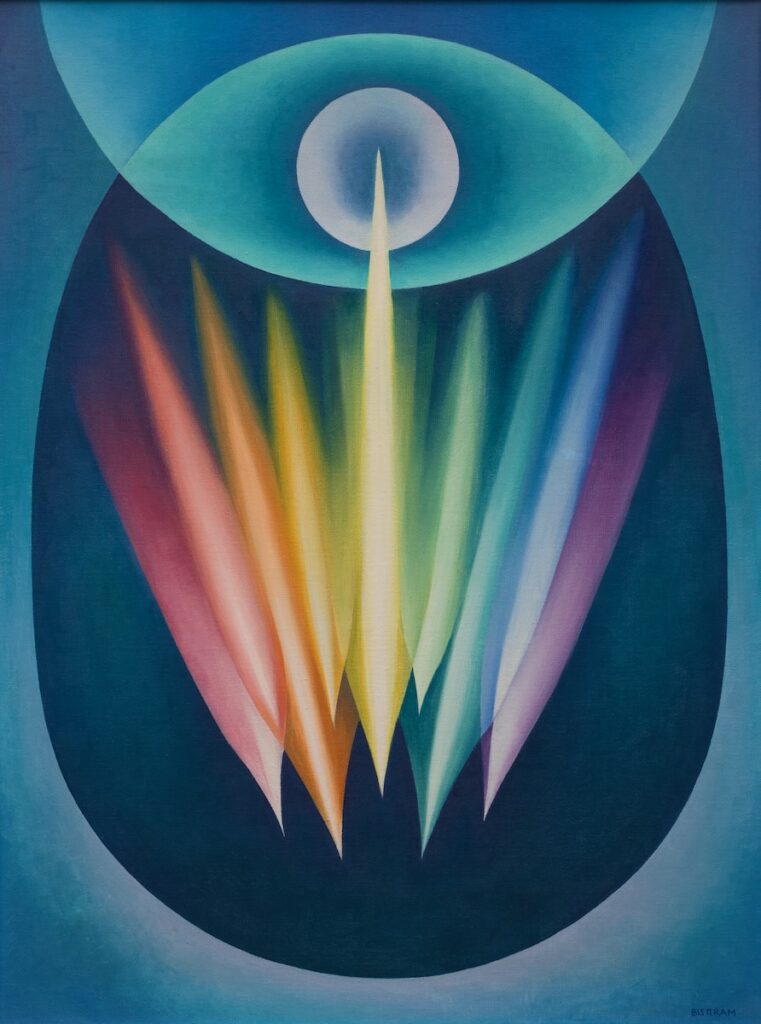

Los Poblanos boasts diverse plantings, from lavender fields to vegetable gardens to pollinator-friendly landscaping. A special rose garden, designed in 1932 by Rose Greely—the first female Harvard landscape architecture graduate—adds romantic charm. Summer blooms make the property magical.

Before leaving, we peeked into the Library Bar, open only to lodgers Sunday through Wednesday evenings. Our staycation had ended too soon, but it certainly will not be our last.

Story by Suzy Santaella

Photography courtesy of Los Poblanos

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine‘s print edition.