Almost 45 years ago, Christine Mather and Sharon Woods wrote Santa Fe Style, a book that captured the unique qualities and sensibilities that give Santa Fe architecture its distinctive look. We sit down with the authors to find out the story behind this seminal, best-selling book to find out that Santa Fe style is alive and well.

The Authors of Santa Fe Style Give the Inside Scoop

“Santa Fe Style is dead. Long live Santa Fe Style.” This is the headline of an article written by Christine Mather for El Palacio magazine in 2013, a full 27 years after she and Sharon Woods wrote the ground-breaking book Santa Fe Style. It’s hard to overestimate the impact that Santa Fe Style had when it was first published in 1986 – how it captured the zeitgeist of the time for those who knew and loved Santa Fe, as well those who longed for a piece of it. Leaf through the book today, and you’ll realize just how relevant it remains.

Sharon Woods (left) and Christine Mather (right).

The Start of Santa Fe Style

While Ralph Lauren was busy in the ‘80s creating an ersatz Southwestern style filled with prairie skirts and faux-Indian blanket coats, Mather and Woods were digging deeper to reveal Santa Fe and the southwest through its architecture. I met Mather and Woods in Mather’s historic home on Acequia Madre. The building started life as a mill, powered by water from the acequia. It’s the oldest part of the house, dating back to around 1800 or perhaps earlier. The house then grew organically – as many homes in Santa Fe have – and is now a showcase for Christine and husband Davis Mather’s enviable collection of folk art.

A bedroom kiva fireplace and host to some of the Mather’s folk art collection.

The warmth and closeness between Woods and Mather is clear, born of spending countless hours creating the book and their shared passion for the subject. They met when Woods (then a builder and designer) was redoing Mather’s former home, also in Santa Fe. Woods remembers Mather asking her, “If we could get along doing a remodel, do you think we could do a book?” Mather was curator of Spanish Colonial Art at the Museum of International Folk Art, from 1975 to 1984 (she was later Curator of Collections at the New Mexico Museum of Art, from 2002 to 2011) but her idea wasn’t for a typical museum book.

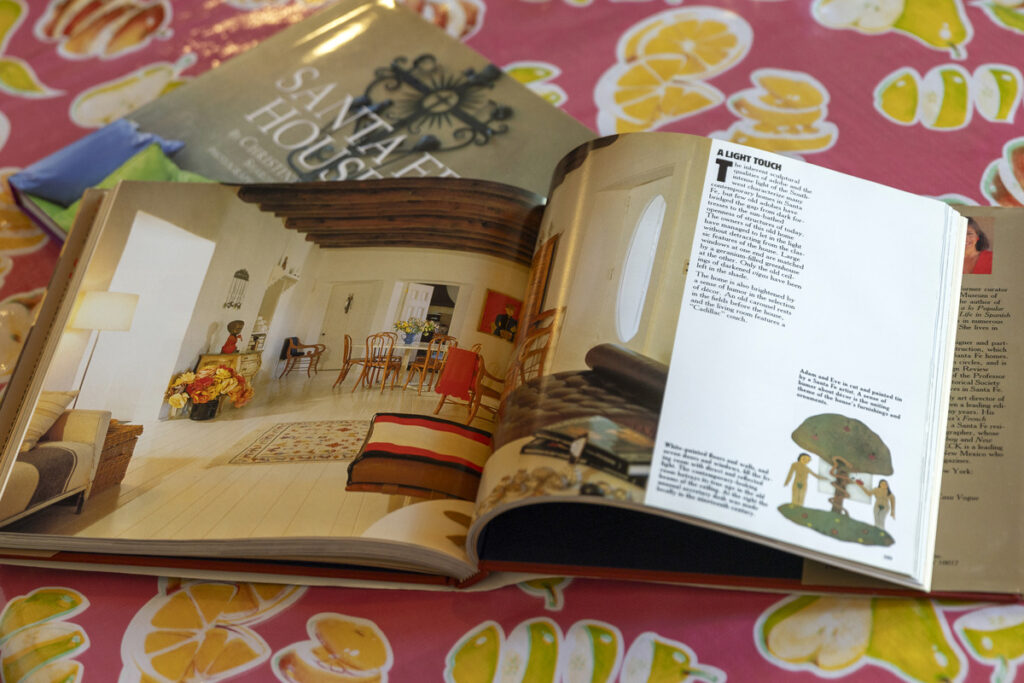

A spread from the iconic 1986 Santa Fe Style book.

Finding the Best of the Best

In a day before cell phones and computers, the duo set out on an analog journey to track down and document the buildings that epitomized Santa Fe style, illustrating their findings with both original and archival photography. They worked with architectural photographer Robert Reck and filmmaker and photographer Jack Parsons (“Thank God we found Jack Parsons,” says Woods) and others. Armed with slides, a detailed business plan, and lots of ideas, they went to New York City. “And we’re stuffed into a phone booth on 42nd Street and we’re trying to get appointments with publishers,” laughed Woods, remembering that rainy day.

Folk art animal statues sit scattered throughout Mather’s home.

They got a book deal but it’s clear that Rizzoli, their publisher, had no idea how formidable the two were or how game-changing their book would be. Published in October 1986, the initial print run of 10,000 sold out in less than two months, and hit the New York Times bestseller list. At that time, it was the top selling book in the publisher’s history, the two recount.

The cover – a photo of a light-streaked adobe wall and a worn wooden table adorned only with an unglazed clay vase, a weathered ram’s skull, and a stone – flummoxed their publisher. “…The Rizzoli people looked at the cover and said, ‘Aren’t there any rich people who live in Santa Fe?’” Mather remembers with a laugh. What they missed, Mather and Woods got. The photo – taken at artist Forrest Moses’ home – was Santa Fe style. As they say in the book, “…these simple, beautiful objects not only created an aesthetically pleasing environment; they also became an artistic enterprise as crucial to Moses as placing pigment on canvas.”

A piece of folk art peaks through a window-way.

Defining Santa Fe Style

Mather and Woods opened the book by looking at the critical impact of setting and also location to the homes that dot our landscape. The importance of light, the native building materials used in construction, walls and fences both for protection and to declare ownership, as well as windows that were virtually absent in original adobe homes but later offered a vista to the outside – these were only a few of the topics they touched upon as they set out to define Santa Fe style. While this style might be difficult to pin down, Mather says we know it when we see it. “It’s identifiable, and we know all the cues, and the cues can be different from time to time, and people keep playing with it,” she says.

Another one of Mather’s fireplaces.

They’re quick to say that style isn’t fashion. It’s actually something deeper that has been developed within our community over centuries and is inextricably tied to place and to history. “It’s how people lived,” Mather says. “Most were looking to be near water. You have to protect yourself from predators. You have to get some sort of heat, and you have to have work areas, and you have to have animals, and gardens, and all the things we’re still working on.”

Folk art decor in Mather’s home.

As they say in the book, “Here man and landscape come together with such mutual benefit that the landscape is brought into human scale, and human inhabitation makes no attempt to master elements beyond its scope.”

Beyond the Bounds of Santa Fe

The homes they captured – mostly in Santa Fe but some further afield in northern New Mexico – not only show us Santa Fe style in action but also provide us with an incredible historical record. Like the home Woods visited where a woman lived who had travelled to Santa Fe in a covered wagon. Upstairs in a bat-filled attic, the woman showed her saddles that had made that journey. “It was an enormous opportunity to get in this house and see these saddles that had come over on the Santa Fe Trail,” Woods says.

Old family photos in frames lay below a beaded Haitian vodou flag in Mather’s home.

And it wasn’t only history covered in Santa Fe Style but also a glimpse to the future with insights into contemporary homes like Charles Johnson’s Boulder House in Scottsdale, Arizona where rocks protrude into the living spaces, blurring the lines between indoors and outdoors and with more than a passing nod to early indigenous cave dwellings and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. Or a passive solar home in Santa Fe designed by architect Robert W. Peters that blends Japanese sensibilities with a distinctively Southwestern feel. “We were looking back and looking forward,” says Mather.

The living room inside Mather’s home.

The Changing of the Times

As the city has expanded, so has the size of homes and with that, a loss of the intimacy that you find in a home like Mather’s. Both authors served on the Historic Design Review Board (now the Historic Districts Review Board) to help ensure that these buildings aren’t lost to over-zealous owners and developers. “The idea is to try and maintain the streetscape, and the streetscape is maintained by individual homes,” Wood says.

While they focused on the architectural elements of Santa Fe style – the rounded shape of a kiva fireplace, the exterior corbels and portales, and the interior vigas and latillas, the two also looked at distinctive decorative arts like tinwork, furniture, and textiles that bring Santa Fe style to life.

A chair leads into a hallway inside Mather’s home.

And while Santa Fe Style captures a moment in time, it has also stood the test of time. “It was a lifechanger for both of us in a lot of ways. I feel fortunate that Christine thought of this, was kind enough to ask me, and that we got to do it,” says Woods. Mather adds, “We were in the right place at also the right time, and we were the right people.”

Story by Julia Platt Leonard

Photography by Gabriella Marks

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.