The Spanish brought San Pasqual, Patron of Cooks and Kitchens, to New Mexico, and he’s made himself very much at home.

San Pasqual, Patron of Cooks and Kitchens

Step into nearly any New Mexico kitchen, whether humble or fancy, and you’ll find the benevolent visage of San Pasqual, the patron saint of cooks. His smiling face, apron, and spoon appear on retablos (paintings), bultos (statuettes), and even tea towels. Often, his image is surrounded by chile ristras, an horno (oven), a pot of beans, or other traditional foods. Sometimes, artists update him with modern touches like grapes, a glass of wine, or even pizza, as shown in Nicholas Herrera’s artwork.

From Shepherd to Franciscan Friar

Paschal Baylón was born on May 16, 1540, in Torrehermosa in the Kingdom of Aragón, Spain. His birthdate fell on Pentecost, inspiring his name. As a boy, he tended his family’s sheep and taught himself to read in the fields. Known for humility and deep faith, he entered the Franciscan order in 1564. He worked as a porter and cook, living with devotion, meditation, and prayer. He died on May 17, 1592, and the Church canonized him in 1690 after miracles were reported at his tomb.

Saints of New Mexico

Spanish settlers carried their devotion to San Pasqual and San Isidro, the patron saint of agriculture, to the New World. Over centuries, both saints became distinctly New Mexican. “The Spanish who first arrived with the conquistadors were mostly townsfolk who didn’t know how to build or farm and had to learn quickly,” explains Nicolasa Chávez, Deputy State Historian for New Mexico. “They turned to Saints Isidro and Pasqual for support and guidance in planting, harvesting, and cooking—critical for survival.”

Harsh winters demanded that dried staples such as beans, chiles, garlic, and onions last through the season. The blending of Indigenous foods with Spanish imports created the region’s distinct cuisine. Saints like Pasqual and Isidro became protectors of fields, homes, and hearths.

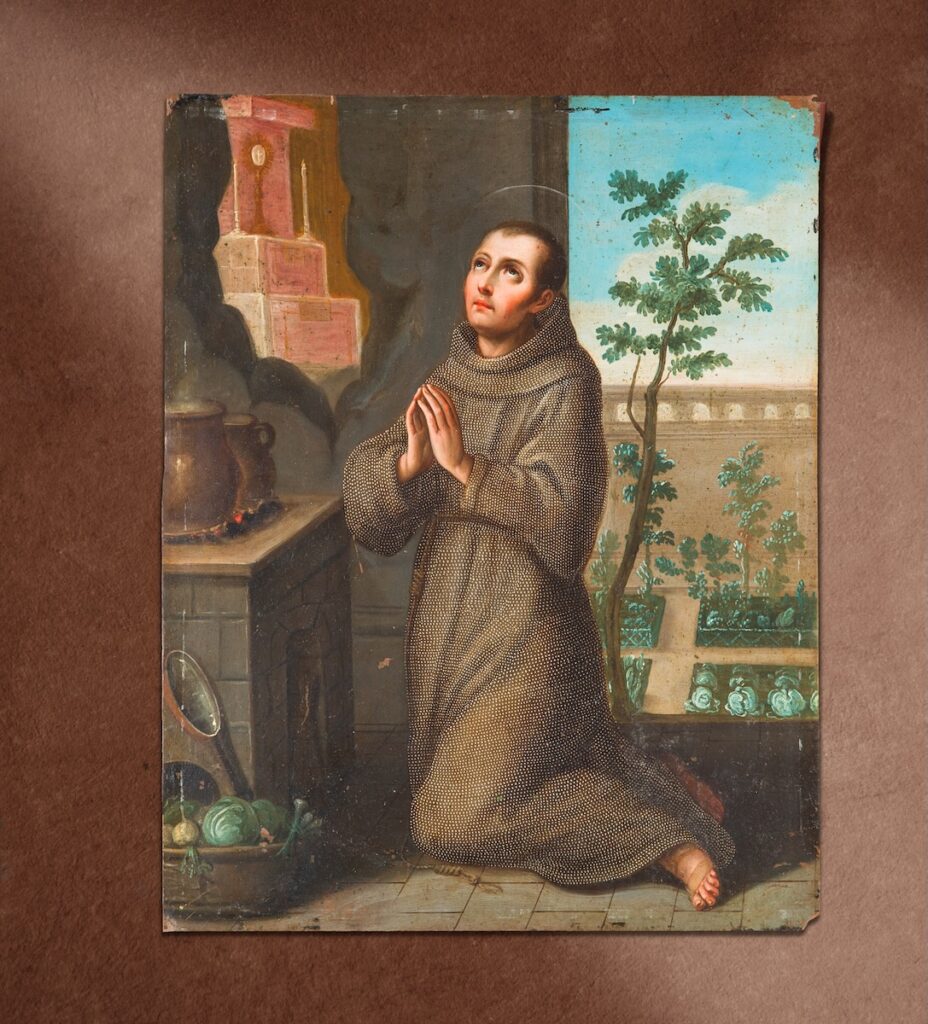

San Pascual, Mexico, 18th century, Collection of the Spanish Colonial Arts Society; 2015.001. // Photo by Blair Clark

The Santero Tradition

Early settlers brought artisans known as santeros, who created devotional retablos and bultos. By the late 19th century, the tradition faded, but a revival in the 1920s and ’30s restored its place in New Mexico culture. Santa Fe’s Spanish Market, founded in 1926, helped preserve these traditions. Today, it is the largest and oldest juried Hispanic art show in the United States, featuring more than 200 artists in 19 categories.

A Cheerful Protector

Depictions of San Pasqual in earlier centuries show a solemn friar in prayer. Over time, however, his image softened into the cheerful, kitchen-friendly saint beloved in New Mexico today. With his apron, spoon, and smile, San Pasqual stands as a protector of cooks everywhere—a friendly reminder that kitchens, like faith, thrive on warmth and care.The depictions of San Pasqual in early New Mexico and in other Catholic traditions are much more saintly—a serious friar kneeling in prayer—but in the centuries since, he has become cheerful and beloved and distinctly ours, with his traditional foods and benevolent smile. San Pasqual resonates with cooks—in the kitchen, everyone can use a friendly protector.

Story by Mara Harris

Photography by Tira Howard

Photography of Historical Image by Blair Clark

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine‘s print edition.