A day in the vault of the Wheelwright Museum yielded glimpses of stunning Indigenous creativity. The sculptures, paintings, drawings, beadwork, and more, had us holding our breath with astonishment. But we exhaled when the museum’s director, Henrietta Lidchi, dove into the museum’s jewelry. It is a privilege to share some of what we saw with you, with Lidchi’s words to put the objects in context. This is the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Go to the Wheelwright with all haste!

Mother Earth is surrounded by rattlesnakes and apple trees. Artist Bob Haozous recalls this as a particularly demanding piece, requiring a lot of precise work and thinking. The apple trees signify environmental activism, drawing from an artist residency in Germany.

Peeking at Jewelry in the Wheelwright Museum Vault

Convention has it that jewelry is merely a beautiful addendum to clothing. But if we pause for a moment and think of it in its fullest sense, we realize that this does a disservice to a dazzlingly complex art form.

A softness is present in these two works by artist Bob Haozous. Both were made as gifts. The portrait of the young woman surrounded by hearts is in the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection. It was donated to the museum by curator, scholar and writer Nancy Marie Mithlo (Fort Sill Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache).

A Historical Look at Jewelry

Two characteristics define jewelry. It is often made of materials thought of as precious, where preciousness can be understood in multiple ways. It can mean that the material is rare or culturally valuable, or it can simply register the sheer labor involved in making a piece that is elegantly simple. Second, jewelry is worn on the body. It is a material interface between the private and the public. As an intimate art form it transforms the wearer into a messenger.

From the 1960s, American art jewelers including Native American jewelers understood the symbolic and political potential of jewelry. Some made work especially to provoke a conversation between makers, wearers, and viewers and grapple with some of the urgent issues of their time. Jewelry was deliberately made to trouble the viewer’s expectations. More mobile sculpture than precious ornament, jewelry was used to express disquiet, critique and protest. Those emerging from art schools harnessed this potential to confound expectations as to what jewelry could be.

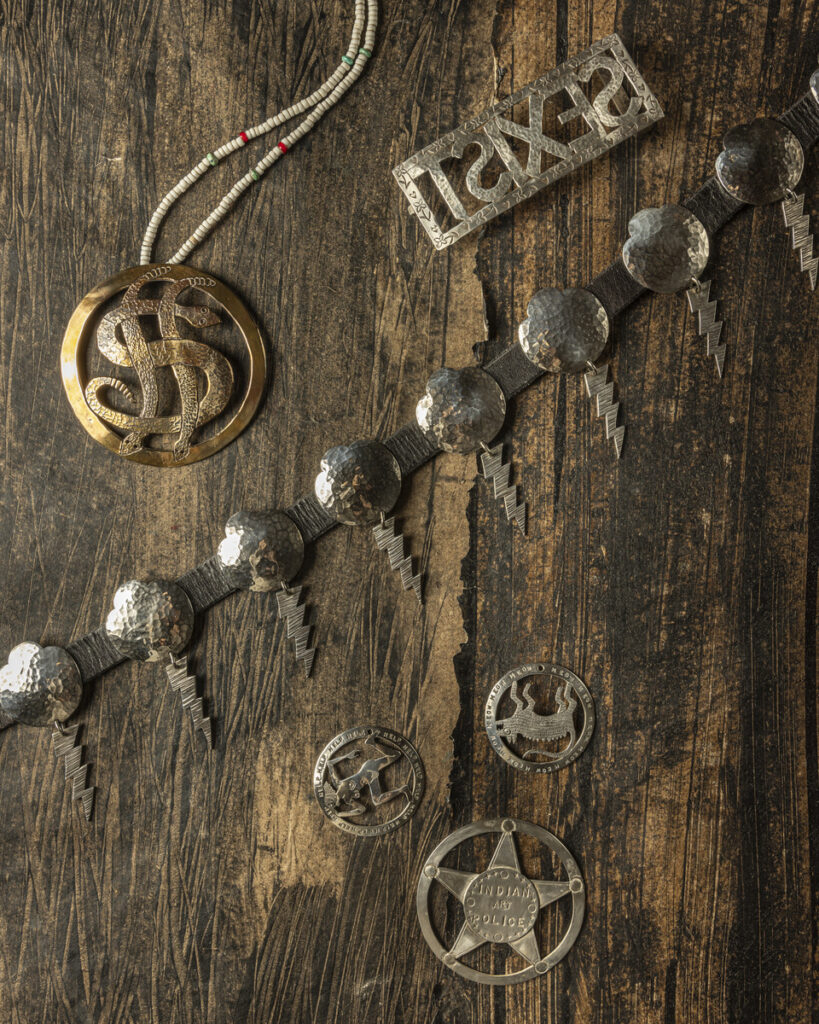

Artist Bob Haozous’s 1990 brass double snake pendant in the shape of a dollar sign is part of a series of pieces originally intended to be a concha belt. His 1989 belt buckle displays the word “sexist” in reverse. His 1991 pendant depicts a woman falling, surrounded by the word “help.” Haozous’s unfinished work from the 1970s is inscribed with “Indian Art Police” and takes the form of a star-shaped sheriff’s badge to level a critique of judges at Native American art shows. The 1987 concha belt with clouds, lightning and buckle with plane reminds us of concerns about acid rain. All but one are in Haozous’s personal collection.

Bringing About Modernity

In 2025, the Wheelwright Museum explores the potential for jewelry as protest in the exhibit Memo to the Mother. This year-long celebration of the work of Bob Haozous (b.1943, Warm Springs Chiracahua Apache) speaks particularly to his environmental messaging, evident across sculpture, jewelry and prints.

Bob Haozous’s female dog wrestling a rattlesnake is in the Wheelwright Museum’s permanent collection, a gift of Charmay B. Allred.

Memo to the Mother focuses on Haozous’s interpretation of the female form. The female nude falling, struggling or running, stands for the embattlement of Mother Earth when faced with the weight of human activity. Asked how he defines his jewelry, Haozous notes that he sees it as a continuum with other work. The divisions between media are mere conventions which potentially dull the capacity for expression. He notes, “In an artist’s studio you cannot let those kinds of restrictions dictate what you want to say, so I just use them all.” Haozous states that his jewelry is a question of expression, not perfection, consistent with Apache aesthetics.

The Wheelwright Museum is fortunate to have a range of work by both Charles Loloma and Preston Monongye in the permanent collection donated by Ann and Lew Stewman and Sidney and Ruth Schultz. The sheer beauty of Monongye’s bracelets is astounding. These were all made between the 1970s and 1980s and recall the excitement that this new jewelry provoked.

A New Period for Native American Jewelry

Haozous’s work emerged in the wake of new directions in Native American jewelry which were embedded by the 1970s. During this period, significant figures came to prominence whose work served to redefine perceptions of Native jewelry. Using the traditional palette of coral, turquoise, jet and white shell, and combining these with novel materials such as ironwood and cocobolo, jewelers produced bold new styles, drawing on the potential of tufa casting.

Hopi jeweler Charles Loloma (1921-1991), himself a graduate of the School of American Craftsmen, was a skilled visionary. Preston Monongye (1927-1987, Mission/Mexican) created dazzling representational compositions. He worked with lapidary artists, such as his son Jesse Monongya (1952-2024, Diné) and Lee Yazzie (b. 1946, Diné). Their work, considered by many to the pinnacle of work made at the time, consciously positioned itself as art jewelry seeking to contest attributions of craft, and to highlight the skill and aesthetic range of Native jewelry.

Loloma’s work has been the focus of more art historical research and the two pieces shown here, the pin of forged silver with turquoise dangles, and the inlaid pendant in female form represent the more restrained work Loloma was making in the 1970s.

Story by Henrietta Lidchi, Director of the Wheelwright Museum

Photography by Tira Howard

Shot on location at Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.