“A hologram isn’t doing anything special,” says C. Alex Clark. “It just shows us what light is doing all the time. Miracles are happening all around us.”

The Santa Fe artist uses high-powered lasers with reflective or refractive objects to capture abstract holographic imagery on emulsion, then embeds the spectral results in glass. Clark’s sculptures shift constantly, changing as you move around them or as ambient light changes. At times, they appear as ephemeral as desert air; at other times, they resolve into swirling forms resembling galaxies, thunderstorms, or retinas.

C Alex Clark, Conveyance Vector 1, 2019. Hologram in hand-ground glass. 6 x 4 x 3 in. Courtesy form & concept.

A History of Light in New Mexico

Many artists have responded to New Mexico’s sunshine-filled, spiritually driven atmosphere by working with light. As Clark prepares for a solo exhibition this January at form & concept, our curatorial conversation has traced this ethereal arc of regional art history.

Among the movements we discussed, the Transcendental Painting Group (TPG) stands out. Active from 1938 to 1942, the circle of ten Southwestern artists propelled abstraction into new emotional and technical realms through their use of light. All but one of the members were based in New Mexico.

The Transcendental Painting Group

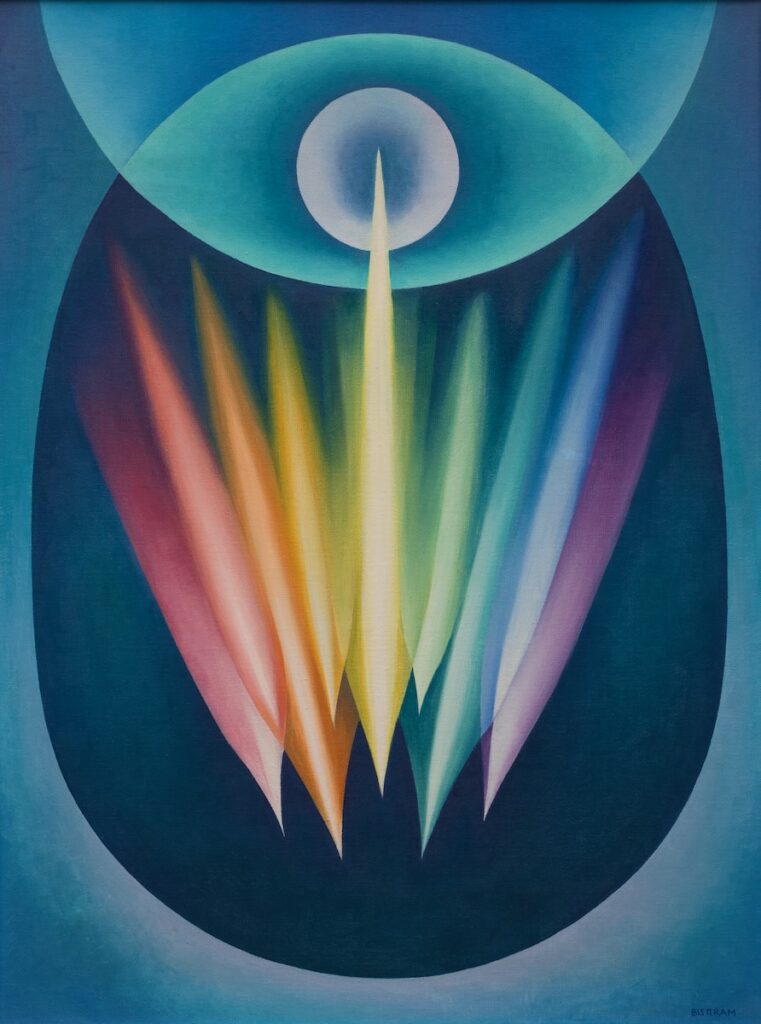

The group’s leading figures—Agnes Pelton, Emil Bisttram, and Raymond Jonson—blended scientific precision with occult wisdom. Their luminous canvases hold forms that deepen and expand as the eye moves through them, surfacing inner worlds that oscillate between ruminative and ecstatic.

Today, exhibitions featuring or influenced by the TPG are appearing across Santa Fe and throughout the nation. Their work feels startlingly timely, reviving ideas about the links between science, art, and spiritual identity. For Clark, this resonance is no surprise.

“It’s cycles of time,” they explain. “The TPG artists were entering a technological age where people were losing sight of what was true within themselves. There was confusion, both internal and external. They were searching for meaning and truth, which I think people are desperate for right now.”

Emil Bisttram, Creative Forces, 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 x 27 in. Private Collection, Courtesy of Aaron Payne Fine Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Apprenticeship and Practice

Clark recently completed a similar search at Santa Fe’s Light Foundry, where they apprenticed for six years under master holographer August Muth. The role required deep scientific study, which Clark approached as a language exercise.

“Once you know the grammar of the material, you can put together a ‘sentence’ that speaks purely beyond words. You can break it, rearrange it, put it back together,” they say. For Clark, light—seemingly the most ephemeral of forces—becomes a sculptural material. The idea surely would have resonated with the TPG.

Scientific and Spiritual Intersections

The New Mexico Museum of Art has hosted two recent traveling exhibitions featuring TPG artists: Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist and Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group. Christian Waguespack, the museum’s 20th-century curator, oversaw significant loans to both. He notes that light was a foundational concern for many TPG artists, often in a more scientific sense than audiences assume.

“We often frame the desire to move beyond the physical in terms of spirituality,” he says. “These artists were interested in that, but maybe not to the extent we think. What is interesting is the almost scientific way the TPG painters show us light as a physical, if not necessarily tangible, phenomenon.”

For example, Bisttram, a Hungarian-American painter with classical training, altered his surname to include the mathematical symbol for pi. He also used the golden ratio in his compositions. For him and other TPG members, light’s dual nature as particle and wave was itself a transcendent mystery.

Still, the group leaned into the esoteric. They studied theosophy, drew from Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art (1911), and sought ways to portray light as both physical fact and symbolic transport.

C. Alex Clark’s Light-Based Art

Like the TPG, Clark aims to evoke complex internal experiences through abstract, light-based art. Light serves as their conceptual tool to explore humanity’s pluralistic nature and to challenge the notion of a spectrum as fixed.

“I think most people are like magenta,” Clark says. “It’s a perceptual color that only exists when blue and red overlap. When you observe a hologram, there’s always a higher-dimensional relationship—you can’t just compare color to color because nothing is purely one color. People inhabit multiple spectrums and planes too.”

A Shared Legacy

Clark’s work at form & concept arrives alongside other light-driven exhibitions in Santa Fe. Vladem Contemporary, the new contemporary wing of the New Mexico Museum of Art, will open this spring with Shadow & Light, curated by Merry Scully.

The show will feature works by Bisttram and Florence Miller Pierce, a contemporary who deeply influenced the group, alongside artists like Charles Ross, Helen Pashgian, Harmony Hammond, Yayoi Kusama, and Virgil Ortiz.

“It’s not that the TPG is the impetus of everything,” Scully explains. “But it seemed a good place to start. Light is both a subject and a material for much of the work. The exhibition looks at New Mexico as a site of opportunity—not because nothing is here, but because everything is here. And two of those things are the light and the land.”

Story by Jordan Eddy

Images Courtesy of form and concept, and Aaron Payne Fine Art

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine‘s print edition.